by: Eric L. Ding

Institution: Johns Hopkins University

Date: February 2006

Abstract

Many American cities, such as Baltimore, are facing modern dilemmas while transitioning from industrial to service-based economies. However, the decline of industry has left many cities with acres of abandoned and potentially contaminated tracts of land, called brownfields, which may pose hazards to human health. Thus, to explore potential hazards, urban economic impact, and strategies for revitalization- we conduct an in-depth case review of the brownfield situation in Baltimore, Maryland. We conducted a systematic review of MEDLINE from 1965 to 2003 to identify all relevant publications using the keywords: brownfield, urban, contamination, urban revitalization; as well as reviewed online Environmental Protection Agency archives, media articles, and conducted personal interviews with relevant public officials in Baltimore. Via a comprehensive assessment of the data, the review concludes brownfield contamination may contribute to excess infant mortality and adult mortality in certain districts of Baltimore, as well as loss of economic activity and productivity as result of fallow brownfields. However, there exist many competing remediation priorities, such restoration for either housing, greenspace, service-based commercial development, or industrial redevelopment. In conclusion, brownfield renewal is a high priority in Baltimore, Maryland. However, all city policy and planning officials need to balance the economic and residential priorities of a city while revitalizing brownfields for the future.

Introduction

In recent decades, Baltimore has experienced a dramatic decline in its industrial base and hence also seen an increase in commercial property abandonment. However, such former-industrial tracts are not always as innocuous as they seem. Many such vacant lands may possess dangerous remnants such as chemicals, hazardous wastes, and other vestigial toxins from their former industrial activities.

The Environmental Protection Agency refers to such vacant properties as brownfields, officially defined as "[sites] the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant" (Brownfields Cleanup and Redevelopment 2003). Brownfield existence imposes many negative ramifications on a local area, including loss of economic productivity, decline in local acreage value, potential detriment to human health, as well as a barrier to future economic redevelopment.

Therefore, for the betterment of local communities around brownfield sites and Baltimore overall, it is important to not only identify the contemporary hazards brownfields may inflict, but also describe methods of amelioration as well as various directions of potential redevelopment. Further, in terms of redevelopment, it is also imperative to delineate the best courses of progress that will balance the priorities of improving economic health and improving community social health. After all, it is as much of a goal to prevent a repeat of pre-cleanup perils after redevelopment, as it is also to achieve improved overall vitality in Baltimore after brownfield redevelopment.

This analysis seeks to explain many of the hazards of brownfields, explore the history and process of brownfield remediation, discuss current brownfield remediation activities in the city, address various redevelopment philosophies and strategies, as well as provide an overall recommendation of how Baltimore should ameliorate its brownfield dilemma.

Scope of the problem in Baltimore

It has been estimated that over 1000 acres of city land is currently being occupied by approximately 100 vacant industrial lots (Paull 2003), constituting over half of all industrial site inventories for the city. Other brownfield experts put the number of industrial sites even higher (Litt & Burke 2002), estimating that there are over 1000 vacant or underused industrial sites throughout Baltimore, 480 of which are each larger than 1 acre in size.

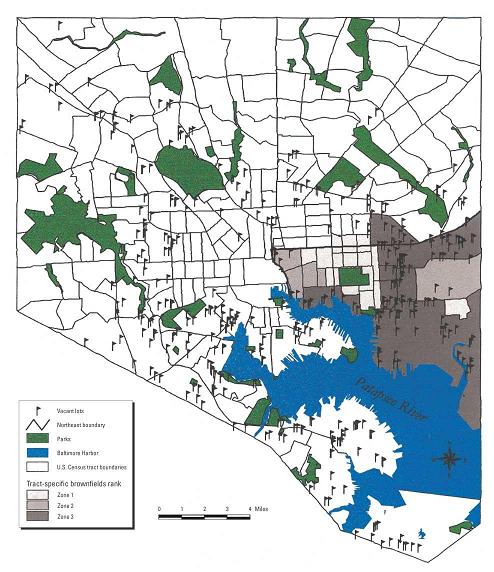

Figure 1. Distribution of major vacant commercial and industrial properties (greater than or equal to 1 acre in size) and degree of brownfield contamination in southeast Baltimore. Source: Litt JS, Tran NL, Burke TA (2002). "Examining Urban Brownfields through the Public Health 'Macroscope,'" Environmental Health Perspectives 110 (2):183-93.

Such pervasive abandonment stems from the dramatic decline of industry in Baltimore in the past few decades. From 1950s to 1990, 66% of all jobs lost in the city during this period occurred in the manufacturing sector of the economy (Friedman 2003; Cohen 2001). This is paralleled by a similar 48% decline of manufacturing jobs in surrounding Baltimore County from 1960 to 2000 (Addison 2003).

Moreover, the waning and eventual bankruptcy of Bethlehem Steel, one of Baltimore's largest employers, resulted in a stark loss of 34,000 jobs during and after its decline (Friedman 2003). With weakening in the manufacturing-sector nationwide and increase in low-cost manufacturing in third-world countries such as China, some believe such industry in America and Maryland will suffer even further decline (Addison 2003). Such weakening in the local industrial base has hence created the current brownfield situation in Baltimore.

Methods

A systematic review was conducting via searching MEDLINE from 1965 through December 2003 to identify all relevant publications using the keywords: brownfield, urban, contamination, urban revitalization. Furthermore, the online archives of the Environmental Protection Agency was carefully reviewed, in addition to media articles. Finally, the author conducted personal interviews with relevant public officials in Baltimore, namely Evans Paull, Director of Brownfields Initiatives of the Baltimore City Development Corporation, and Dr. Nkossi Dambita, director of the mortality registry maintained by the Baltimore City Health Department. Based on information obtained on the systematic review, and comprehensive assessment, the current brownfield situation in Baltimore is summarized, and strategies for revitalization are proposed.

Results

Health Effects of Fallow Brownfields

From a simple perspective, one might ask: what exactly is so dangerous and unethical about leaving a former-industrial property idle? While it may seem that these unused lands do not cause harm, the truth is that the continued existence of fallow brownfields has major detrimental effects on human health and the economy.

Because brownfields may potentially be contaminated by industrial wastes and toxic chemicals, there is reasonable biologic plausibility that such pollutants may harm humans. This can potentially occur through increased local exposures to volatile chemicals emanating from a contaminated site, leaching of toxins into the surrounding soil, which vegetable gardens of local residents may absorb, or perhaps through children exploring and playing on the brownfield site and directly coming into contact with such chemicals and industrial wastes. Any such hazardous exposures may result in serious detrimental effects on the health of local residents.

Figure 2. Brownfield sites in southeast Baltimore, with top 10 hazard-score sites highlited. Source: Litt JS, Tran NL, Burke TA (2002).

Such scenarios of exposures from industrial sites and toxicological effects have not only been affirmed by experts as plausible and likely (Evans 2002), but they have also indeed been corroborated by research and historical events. One study found that increased residential proximity to industrial sites contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) is associated with higher rates of low-birth-weight infants (Baibergenova 2003). PCBs were, in fact, one of the categories of toxins found by researchers analyzing Baltimore brownfields (Litt & Tran 2002). Additionally, other research by Ding et al. (2005) has shown that such environmental pollutants found in brownfields may contribute to the high infant mortality rate in Baltimore, MD.

However, the most infamous and defining incident in United States history that highlighted the horror of industrial contamination was the 1978 episode in the Love Canal community of Niagara Falls, NY (Beck 1979). Formerly utilized by Hooker Chemical Company to dispose of many steel drum filled with toxic materials, the company simply paved over the highly polluted acreage and sold the land in 1953 for $1 to the city, which the city subsequently developed for a residential neighborhood and elementary school. Later in 1978 after record rainfall, barrels upon barrels of the buried chemicals upwelled to the surface, leaking their toxic compounds throughout the neighborhood,from the streets, to backyards, to basements, into soil, and even to school playgrounds. In addition to pervasive noxious fumes, many children acquired acute chemical burns, and significant numbers of children were born with congenital birth defects. After storms of protests and national attention, all local families were eventually relocated out of Love Canal and multi-million dollar cleanups were implemented by the federal government.

Though most brownfields are not nearly as contaminated as Love Canal, this "most appalling environmental tragedy in American history" (Beck 1979) demonstrated the potential dangers of reusing former industrial land where little is known regarding previous levels of industrial pollution and toxic contamination. However, there has been more recent research linking brownfield density to excess mortality in areas of Baltimore as well.

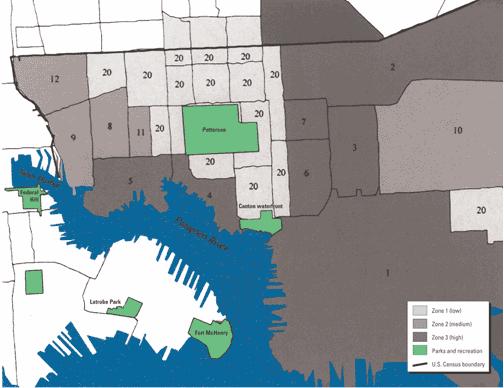

Figure 3. Census tracts shaded with respective brownfield hazard zones (dark=3). Source: Litt JS, Tran NL, Burke TA (2002).

A group of researchers from Johns Hopkins University also previously examined the association between the level of past industrial contaminations in brownfields of southeast Baltimore and census-tract specific mortality rates (Litt & Tran 2002). By ranking census tracts 1, 2, and 3 (3=high) for the levels of calculated brownfield contamination, and using official data from the Baltimore City Mortality Registry, Litt and colleagues found statistically significant higher rates of mortality (Odds Ratio [OR]= 1.20, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.10-1.31; P less than 0.0001) and all-cause cancer mortality (OR= 1.27, 95% CI: 1.09-1.48; P=0.002) in the highest brownfield zones (=3) compared to the low-brownfield-contamination zone. Additionally, adverse effects on respiratory distress were also seen from the results. A summary of the relevant Baltimore census tracts are shown in Figures 2 and 3, and results shown in Figure 4.

The study by Litt and colleagues, demonstrating a significant 20% increase in mortality (P less than 0.0001), 27% increase in cancer mortality (P=0.002), 33% increase in lung cancer mortality (P=0.03), and 39% increase in respiratory mortality (P less than 0.001) among residents in higher brownfield hazard zones, strongly corroborates the theory that brownfields are detrimental to human health. Though ecologic fallacy may play a role, there is still highly suggestive evidence considering the circumstance of why significantly higher mortality was found in the areas with more hazardous industrial activity. Therefore, in the very least, there exists the continued possible threat of potential detrimental health effects from existing idle brownfields.

Economic Implications of Fallow Brownfields

While health impact may be a speculated consequence of brownfields, there is virtually no debate regarding the economic ramifications of idle brownfields. According to official EPA estimates ("Brownfields 2003 Grant Fact Sheet" 2003), Baltimore loses approximately $26 million a year in lost tax revenues from abandoned and underused brownfield land.

Such a tremendous loss of economic potential from brownfields takes into account the estimated loss of income from commercial property tax, loss of economic development investment, and loss of production of goods and services. Additionally, the economy in Baltimore also suffers from loss of employment and social revitalization as result of brownfield underdevelopment. Moreover, vacant lots and fallow brownfields without economic vitality also decrease local property values (England-Joseph 1995; Greenberg 2002).

From an investment perspective, brownfields impose two additional barriers to redevelopment. First, the potential of dangerous contamination is enough to discourage companies from being willing to develop and reuse the brownfield land (Schoenbaum 2002). Second, even if companies are willing to invest in cleanup and redeveloping brownfield land, financial institutions, insurance companies and other creditors are unlikely to be willing to provide loans and funding for such projects out of fears of hazard liability (England-Joseph 1995). Thus, fallow brownfields likely have adverse implications on the economics of the local geography.

Funding Programs for Brownfield Remediation

Environmental site assessment, site cleanup, hazardous waste disposal, contamination prevention, and future environmental monitoring all require significant amounts of financial assets just so that redevelopment can begin. Thus, many funding programs, investment enticements, and policy incentives have emerged over the years to help companies and individuals overcome many of the obstacles in redeveloping brownfields.

The brownfields dilemma has not always been a prominent issue in America. Before the Love Canal incident, there were no major federal initiatives aimed at helping cleanup of industrial contamination. First, the only federal programs that existed during and before Love Canal (Beck EC 1979) were: the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), Clean Water Act (CWA), Clean Air Act (CAA), Pesticide Act (PA), and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). However, the first four acts only involved regulation of toxic substance use and discharge (TSCA 2003; CAA 2003; CWA 2003; PCA 2003), while RCRA only assisted in disposal issues of municipal and hazardous waste landfills (RCRA Cleanup 2003). However, none of the programs focused on cleanup of former industrial land.

Figure 4. Odds ratios of mortality rates, stratified by various causes of death, between different brownfield hazard zones, in persons less than or equal to 45 years old, 19901996. *Note: multivariate adjustment of OR done for factors of population age, area of census tract, and significant SES indicators. Source: Litt JS, Tran NL, Burke TA (2002).

Eventually after the Love Canal tragedy, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) was enacted by the EPA in 1980 as the primary statute regulating the actual cleanup of "inactive hazardous substance sites" (CERCLA 2003). Known more commonly as the Superfund, the program focused on cleaning up contaminated industrial sites. However, a long, bureaucratically complex process dictates each of the steps, such as which sites undergo preliminary assessment, site investigation, expanded assessment, archived waitlist, and eventually listing on the "National Priority List" of the Superfund program to begin cleanup (Reinvesting. 2003; CERCLA 2003).

In addition to the reality that too much bureaucratic regulation existed for using Superfund for industrial cleanup , most brownfields would likely never make the National Priority List (Paull 2003), since the Superfund program was originally designed for the cleanup of large scale hazardous site and not specifically for scattered former-industrial sites. Additionally, Paull adds that Superfund statutes stipulate a liability policy that "once you own it, it's your fault", leaving hazard liability wide-open for future investors, and thus discouraging redevelopment. Thus, the perceived liability hazard of brownfields continued to persist.

Reform and enactment of new legislation to address brownfields did not arise until 15 years later, when the Clinton Administration reinvigorated the EPA and environmental policies. In the mid 1990s, with industrial decline becoming more evident on a national-scale, the liability hurdle became a more addressed nationwide. A "revolution" swept across the country in which state governments began creating voluntary cleanup legislations to not only promote redevelopment of brownfield areas, but also absolve liability dilemmas (Paull 2003).

As part of this revolution, Maryland state government enacted its Voluntary Cleanup Program (VCP) in 1997, which the state touts as being able to "streamline the cleanup process. provide liability protection. and encourage transfer of properties" for development (VCP 2003). However, Paull (2003) notes a caveat that though VCP provides liability protection, it also sets cleanup standards for specific future uses. Thus, if one uses the land for future activities not respective to its minimum cleanup standards, then the liability protection granted by VCP would be voided (VCP 2003). However, VCP does encourage to the primary "inculpable" entity to volunteer for cleanup, as well as provide liability relief for financial lenders, thus facilitating future development of such sites (Brownfields Initiative 2003). Nevertheless, the VCP program is not free of a complex process that requires a long timeframe for completion (Paull 2003).

Ever since the "revolution" of voluntary cleanup programs in states nationwide, experts agree that there has also been significant federal political attention focused on brownfield renewal in recent years (Greenberg 2003). During the Clinton Administration in 1997, Vice-President Al Gore announced the Brownfield National Partnership (BNP) to streamline the coordination of many government agencies to together tackle the issue of brownfields, as well as highlight 16 showcase cities to display their local efforts (Brownfields Showcase Community Fact Sheet 1998). Though this appeared ambitious, Paull (2003) noted that BNP did little except facilitate resource access and elevate the national prominence of the brownfield issue.

Though brownfield reform was seen as necessary, Republicans in Congress held the issue of brownfields in the Superfund and environmental reform package "hostage" for several years (Paull 2003). Though the Bush Administration eventually persuaded GOP members to pass the Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfield Revitalization Act (SBLR-BRA) pass in 2002 (Paull 2003), such legislation was passed for the sole purpose in promoting business via absolving liability rather than actual environmental cleanup. Particularly, the legislation established a controversial new method to more easily and efficiently obtain liability relief for companies. Based on a self-administrated "affirmative defense", the legislation allows companies to legally obtain automatic self-liability relief without any formal approval or oversight from the EPA, or state agency. The only requirement to obtain a liability waiver is for private companies to carry out their own "appropriate" site assessments, self-determined level of cleanup, and own self-assurance to prevent and protect the land from future contamination (Brownfields Initiative 2003; Paull 2003). Such nebulous and inexact language of the legislation is captured by ambiguous terminologies such as: "appropriate inquiries. reasonable steps. generally accepted. customary standards and practices." (Brownfields Initiative 2003; Summary of the SBLRBRA 2003) Though this independent process is very efficient in obtaining legal liability relief, it adds much uncertainty in whether or not legitimate or sufficient cleanup was actually conducted.

Nevertheless, the Brownfield Revitalization section of the SBLR-BRA reform indeed pumped more federal funding into brownfield-specific cleanup grants and loans. It sets up a maximum of $200,000 for brownfield site assessment, $1 million in revolving loan fund grant for cleanup, and/or another $200,000 grant directly for remediation (Brownfield Initiatives 2003). Of the opportunities, the Baltimore Development Corporation was recently awarded a $1.2 million site assessment and revolving loan grants (Brownfields Grant Fact Sheet 2003).

Other EPA, HUD, and Maryland State Funding for Brownfields

Besides the new funding created by the enactment of SBLR-BRA, there are a host of other federal and state funding programs. Within the EPA, there exists additional brownfield assessment grants of up to $700,000, job training grants of $200,000 for surrounding areas, underground petroleum storage brownfield grants of $100,000 for former gas stations, and specific funding under the old RCRA program to prevent underused hazardous waste and landfill sites from becoming idle brownfields and to directly promote their redevelopment ("Brownfields Cleanup and Redevelopment" 2003). Though there existed Community Development Block Grants (Bartsch 1996) before 2005, such funding was not renewed and eventually terminated by the Bush Adminstration.

In terms of local programs, there exist many state-administered programs to assist with funding cleanup actions of the VCP and developing in brownfield areas of Baltimore. These include the Maryland Brownfields Revitalization Incentive Program (BRIP) to fund site assessments and cleanup, Port Land Use Development Zone Federal Fund for areas in the "port development zone", Water Quality State Revolving Loan Fund, Neighborhood Business Development Program for providing loans to companies locating or expanding in revitalized areas, Baltimore City Enterprise Zone Tax Credit for companies locating in such enterprise zones, as well as Maryland Economic Development Incentives providing up to $5.5 million in tax credits for locating sufficiently large businesses in Baltimore, in addition to funding programs for their development (Brownfield Initiative 2003).

Recent Brownfield Redevelopment Activities

Given there are incentive programs to support remediation, it is now important to consider the recent state of redevelopment in Baltimore and ponder what prospective changes Baltimore should adopt its future redevelopment efforts. According to Maryland Department of the Environment (VCP 2003), as of January 2002, 49 brownfield sites (439 acres) in Baltimore have gone through the VCP program since it was enacted in 1997. Evans Paull (2003) puts the number of brownfield sites who have gone through cleanup currently at 100 sites throughout the city [as of November 2003].

It is important to note that after brownfield cleanup, there are still significant follow-up safety measures and guidelines to which companies must adhere (Paull 2003). First, for any contaminated site, there must be vapor barriers put into place to prevent any vestigial chemicals from seeping up. Other rules that apply include institutional controls not to dig and deed restrictions limiting the later land activities that may take place. Further, the Maryland Dept of the Environment is required to periodically check for the continuance of a visible barrier as well as adherence to the restriction activity guidelines. However, Paull does concede that there is always the danger of breaching some of these safety guidelines whenever underground utility work needs to be performed. Further, he also adds that with the number of remediated brownfield sites ever increasing, the continual and regular monitoring of such safety conditions will become ever more difficult.

This list of sites having undergone, or currently undergoing remediation is extensive. However, Paull (2003) estimates that over 50% of cleaned-up sites have gone back into industrial activity, 40% into other non-industrial commercial activity, while only a small percentage have gone towards neighborhood development activities. However, such allocation of uses is not necessarily the most optimal distribution of redevelopment activities for Baltimore. Thus, where should Baltimore's priorities lie for future brownfield redevelopment?

Potential Areas of Brownfield Redevelopment

As Baltimore comes to a turning point in its history where it can help decide the future fate of the city, one most appropriately consider what would be the best focus of brownfield redevelopment. Among the options, the possibilities include: supporting the old industrial-base, facilitating service-based commerce, enhancing community and housing, or even rejuvenation of sites back into greenfields and parks. To better understand the options, the pros and cons of these possibilities must be weighed.

Industrial Development Pros. Since a large number of the brownfield sites overall are already existing in industrial zones (Brownfields Grant Fact Sheet 2003), one can argue that redeveloping remediated brownfield land back into industrial uses would seem logical. Additionally, as Paull agrees (2003) that industry generally provides more job opportunities than other economic activities. Furthermore, such jobs that are created by industry would typically be low-skill labor and able to employ a large sector of Baltimore's low-education workforce, thus helping to stimulate the local economy and also perhaps add vitality back into the local communities. Cons. As stated at the beginning, one major problem with focusing on industry is that industry and manufacturing is already on the decline in America. Continuing to narrowly focus on industry would be poor economic forecasting. Paull (2003) concedes that attracting industrial companies is currently a difficult prospect indeed. Additionally, redeveloping brownfields for industrial purposes would likely begin again a vicious cycle of potential contamination followed by abandonment in future years back into a fallow brownfield. After such efforts to remediate the brownfield and redevelop it, it might be questionable to zone the area for heavy industry again. Other Issues. In terms of reconverting land back into industry,such prospects are not always possible after brownfield remediation. Often times, land use controls and regulations prohibit reuse of such land for heavy industry after rehabilitation (Turning brownfields green again 1996). In addition, a Baltimore Business Journal (Harlan 2000) report suggests such industrial redevelopment is not a priority with Mayor O'Malley. On the other hand, the Dept of Planning's PlanBaltimore! (1999) draft does outline a plan to redevelop 30% of Baltimore's industrial land and to continue to implement brownfield conversion back into industrial land. Service-Based Commerce Development Pros. Non-industrial commercial activity is not likely to pollute the environment as much as heavy industry would. Additionally, certain areas like the technology sector would like increase in the future, if not already be emerging in Baltimore (Snyder 2000). Additionally, such employment would be likely higher-paying and better able to boost the local tax base. Cons. Although serviced-based financial and technology sectors might bring more high-paying jobs than low-skill jobs, the overall undereducated Baltimore population would likely be locked out from such opportunities in the short run. As result, the trickle-down effect of positive community impact would also likely be limited. In addition, it is important to note that many high-paying workers who are hired would most likely not live within the city boundaries, and instead commute from the suburbs. Such suburbia preferences of those with higher SES outside of city-limits would result in Baltimore not fully capturing the potential tax-base revenue. Other Issues. Even though there are signs the technology sector may be emerging (such as with the construction of the new biotech park near Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions) and Mayor O'Malley strongly supporting it as a priority for development (Harlan 2000),others concede that it may be difficult to attract tech investors to Baltimore (Sun staff 2000). However, service-based commerce does indeed seem likely as a top area for future Baltimore development, especially with PlanBaltimore! (1999) listing the support and growth of the tech sector as a major step in strengthening Baltimore's position as a "global city". Housing and Community Development Pros. Much of the city's housing units are old, dilapidated, and often contaminated with lead (Friedman 2003). Therefore, there is a need in the city for brand new, safe, and clean homes for residents. Additionally, redevelopment of new communities offers the chance to remove slums and blight from a neighborhood, as well as bring in more residents and add to the income tax base (Greenberg 2002). Greenberg, from his research, also adds that developing affordable housing is also necessary in areas where land-competition is intensive. Furthermore, residential-related retail stores such as nearby grocery stores are in short supply, and redevelopment often neglects construction of such badly-needed produce stores tailored to local residents (Perdue 2003). Thus, the development of such community related structures would be a beneficial to such areas. Cons. However, in regards to potential investor-greed and eagerness to redevelop land, "grave concerns" remain regarding the reliability of developer-initiated cleanup (Greenberg 2002). It is important to note from the Love Canal incident that safety assurances of previous manufacturing companies are not always reliable. Therefore, inadequate cleanup might leave residual health hazards in such remediated areas. This is particularly a concern in light of the new self-administered, self-initiated, and self-affirmed cleanup practices under the Bush Administration's liability relief act. In addition, redevelopment for housing would often be unlikely due to the nature of brownfield cleanup programs and funding (Paull 2003), which virtually all favor compensation and support to businesses rather than individuals. Furthermore, an argument often raised in opposition to housing development is that there are already rampant housing vacancies throughout Baltimore (Friedman 2003). Therefore, one can easily argue that newly remediated land should mostly be dedicated to other economic activities Renewal into Greenfields and Parks Pros. Though transforming a brownfield back into a near-pristine greenfield seem unlikely, there exists potential for such remediation. With increasing scientific innovations and discoveries, we are more able to decontaminate land and restore the terrain back into a more natural earth-friendly environment. In addition to traditional chemical cleanup methods, recent advancements in environmental engineering have demonstrated that solutions such as simple, finely-grinded iron powder can be pumped into contaminated land to break down substances such as dioxins, PCBs, and other toxic agents into innocuous compounds (Svitil 2003).

Recently, scientists have also unearthed a new variety of microbe that literally "dines" on toxic waste (Robbins 2004). Tested with the ability to breakdown, within 6 weeks, an entire site contaminated with vinyl chloride, a high priority EPA toxin present in 1/3 of all toxic waste sites nationwide , such bacteria show promise in naturally rejuvenating certain brownfield sites. In addition, scientists have also discovered that certain trees can grow and thrive in contaminated land, even uptaking and removing heavy metals from the soil. The researcher even specifically alluded that sustained woodlands may even be possible for brownfields (Dickinson 2000).

Finally, according to the city Dept of Recreation and Parks ("Partnernship for Parks" 2003), research has also shown that physical environment such as parks, have significant impact on real estate values, economic development, reduction of public costs and positive social behavior , as seen in Boston, New York and Chicago. The greenspace option is also appealing given that, compared to nationwide, Baltimore ranks poor in density of city parks per 1000 residents (16th out of America's 25 largest cities) ("Kid Friendly Cities Report Card" 2000). Moreover, Baltimore likely ranks much worse in this category due to the inflation of the value of 7.8 acres/1000 person statistic as result of sharp population decreased in the city over past decade (Friedman 2003; MDHMH 2002)]. Additionally, Baltimore's CitiStats database (2003) shows that, with exception of Patterson Park, there are no green-space parks in all of southern and southeast Baltimore.

Cons. Of course, there are also reasons why such greenspaces may not be efficacious. First, using former brownfield land for parks offers the greatest risk for exposure of humans to vestigial contamination leftover from all the artificial and natural renewal process. Secondly, phytorejuvenation is a very slow process and can take a longer time than deemed feasible by most urban planners. Thirdly, greenspaces might not be the most important type of development in an area that is land intensive, or starving for development of its economic base. Finally, in face of tight budgetary constraints, the development of more parks in Baltimore is doubtful given the city's Dept of Recreation and Parks admits there is even inadequacy in the current funding of existing parks and recreation sites in the city ("Partnership for Parks" 2003).

All in all, experts indeed conclude that cities should "adopt policies that better link redevelopment with community needs [and priorities]. (Levine 1987)"

Balancing Redevelopment Priorities for Human Health

Before public officials make an overall judgments and decisions regarding the priorities of future brownfield redevelopments, the potential ramifications on human health must be weighed and considered. For example, because Baltimore's Brownfield Initiatives are managed by the Baltimore Development Corporation (BDC), such policy makers push that economic benefits are the top priority (Paull 2003), overruling assessing effects on human health. Thus, consideration of effects redevelopment on human health is also necessary.

Compared to federally-funded projects, environmental impact statement standards of local commercial developments are not as rigorous, formal, or necessarily even existent (EIS 2003; NEPA 2003). As previously recognized, environmental impact statements are usually little more than educated guesses, and do not fully acknowledge or delineate all potential hazards (Harvey 2000). Furthermore, the fact that many residential neighborhoods are intermingled among industrial areas in Baltimore ("Brownfields 2003 Grant Fact Sheet" 2003) only heightens the sensitivity of potential brownfield effects on the health of local residents.

The great irony that policy officials and redevelopers should avoid is inducing equivalent or greater levels of adverse health effects after redevelopment as compared to pre-development of a fallow brownfield. Even if we making the strong assumption of no residual ground pollution from industrial toxic disposal , there still remains the increase likelihood of air pollution. Air pollution can not only come from smokestacks of factories, but also from increased emissions from vehicular traffic as well. Increased urban air pollution in turn can increase morbidity as well as mortality (Brauer 2002) in the local population, especially infant mortality by increasing the incidence of infants with low-birth-weight, congenital birth defects, and of course respiratory distress (Woodruff 2003; Ritz 2002; "Urban air pollution." 2002; Ding 2005).

It should be pointed out that Baltimore is not only ranked as the city the 7th worst air pollution in the nation (Atlas 2003), but also a city that has consistently failed ozone clean air standards, according to the Maryland Dept of the Environment ("Maryland Dept of the Environment" 2003). Additionally, research from Baltimore also indicates that low SES individuals indeed reside closer to industrial air pollution (Perlin 2001). Thus, air pollution consequences must be further exacerbated for such individuals, especially if they live in areas with high-density of commercial redevelopment.

To deal with such potential air pollution dilemmas, urban planners and developers should design ways to reduce traffic and its associated air pollution. Lessons from the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, GA shed evidence that measures to reduce traffic and preparation for urban influx can indeed decrease ozone pollution and subsequent morbidity (Perdue 2003). Therefore, there needs to be other preventative measures taken such as designing a more adequate and popular mass-transportation system in Baltimore, in which the current transportation system suffers from unpopularity and decline in ridership (Cox 2002). Additionally, such measures may also prevent traffic related injuries and deaths (Bunn 2003).

Furthermore, it should also be addressed that the demolition of buildings for redevelopment itself can increase dust and respiratory irritants in surrounding areas, thus increasing health risks. This has been confirmed not only from external research (Brown 1987), but also research specifically arising from Baltimore (Farfel 2003; Beck 2003). While liability for such demolition hazards are waived if the companies performs such brownfield remediation under the VCP (Paull 2003), city officials and developers should adopt the public health philosophy and still take every precaution to minimize such harmful health exposures during the redevelopment process.

On the other hand, redevelopment can also have positive impacts on health as well. From a macroeconomic view, the obvious trickle-down effect of local economic development could also bring about positive changes in the SES and welfare of the locally population. However, development in an inner city area prevents metropolitan sprawl. Research have indeed found that increased in urban development density (or decrease in sprawl) is associated with decreased rates of traffic and pedestrian injuries and fatalities (Ewing 2003). Regardless of whether or not such an association is causal, such phenomenon reflects the general structure and direction of economic developments that brownfield redevelopment helps promote.

However, it is finally important to again emphasize the avoidance of inducing a paradox of adverse health effects as result of brownfield remediation. In the end, if public officials cause more detrimental harm after brownfield remediation than before redevelopment,then we will only have achieved an empty Pyrrhic Victory. Therefore, to combat the brownfield situation in Baltimore and other cities with similar plights, a balanced strategy of redevelopment should be ultimately adopted to bring about improvements in both economic and social health in an equitable manner to bring prosperity for all.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the support of Dr. Nkossi Dambita of the Baltimore City Health Department, Dr. Sandra Newman and Ms. Marsha Schachtel of the Johns Hopkins University Institute for Public Policy, and the Abell Foundation for their support of this project.

References

Addison, Eric (2003). Retooling for a new reality. Baltimore Sun. July 28. December 10.

Atlas, Steve (2003). Reduce Air Pollution and the Number of Ozone Days, Baltimore City Department of Transportation. November 1.

Baibergenova A, Kudyakov R, Zdeb M, Carpenter DO (2003). Low birth weight and residential proximity to PCB-contaminated waste sites. Environ Health Perspect 111, 1352-7.

Baltimore City Health Department, Office of Grants, Research, Surveillance, and Evaluation (2003). Baltimore City Mortality Registry.

Bartsch C, Collaton E, Pepper E (1996). Coming Clean for Economic Development: A Resource Book on Environmental Cleanup and Economic Development Opportunities. Washington, DC: Northeast-Midwest Institute.

Beck CM, Geyh A, Srinivasan A, Breysee PN, Eggleston PA, Buckley TJ (2003). The Impact of a Building Implosion on Airborne Particulate Matter in an Urban Community, Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, October.

Beck, Eckardt C (1979). The Love Canal Tragedy. EPA Journal, Janurary 1979. Environmental Protection Agency. December 10, 2003.

Brown P, Mayer B, Zavestoski S, Luebke T, Mandelbaum J, McCormick S (2003). The health politics of asthma: environmental justice and collective illness experience in the United States, Soc Sci Med 57, 453-64.

Brown SK (1987). Asbestos exposure during renovation and demolition of asbestos-cement clad buildings, Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 48, 478-86.

Brownfields 2003 Grant Fact Sheet (2003). Baltimore Development Corporation, Environmental Protection Agency, October 15.

Brownfields and Redevelopment Financial Assistance (2001). Manko, gold, Katcher, & Fox, LLP, November 1, 2003. Brownfields Cleanup and Redevelopment (2003). Environmental Protection Agency, November 2.

Brownfield Initiative (2003). Baltimore Development Corporation, November 3.

Brownfields Showcase Community Fact Sheet (1998). Baltimore, Maryland, Environmental Protection Agency, October 28, 2003.

Brauer M, Hoek G, Van Vliet P, Meliefste K, Fischer PH, Wijga A, Koopman LP, Neijens HJ, Gerritsen J, Kerkhof M, Heinrich J, Bellander T, Brunekreef B (2002). Air pollution from traffic and the development of respiratory infections and asthmatic and allergic symptoms in children, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166, 1092-8.

Bunn F, Collier T, Frost C, Ker K, Roberts I, Wentz R (2003). Area-wide traffic calming for preventing traffic related injuries, Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD003110.

(CAA) Clean Air Act (2003). Environmental Protection Agency. December 10.

(CERCLA) Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (2003). EPA, December 10.

[CIP] Capital Improvement Projects (2003). Baltimore City Dept of Planning, December 10.

CitiStat Reports and Maps: Dept of Recreation and Parks (2003). Baltimore CitiStat website, December 10.

Cohen, James (2001). Abandoned housing: exploring lessons from Baltimore. Fannie Mae Foundation: Housing Policy Debate 12, 415-448.

Cox, Wendy (2002). The truth about transit, Baltimore Sun, July 7.

(CWA) Clean Water Act (2003). EPA, December 10.

Dickinson NM (2000). Strategies for sustainable woodland on contaminated soils, Chemosphere 41, 259-63.

Ding, EL. (2005). Infant Mortality in Baltimore City: Leading Causes, Risk Factors, and Potential Policy Solutions. Epidemic Proportions 2, 38-43, 57-59.

[EIS] Environmental Impact Statements (2003). Environmental Protection Agency. December 12.

England-Joseph JA (1995). Community development: reuse of urban industrial sites. United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chair, Committee on Small Business, US House of Representatives.

Evans GW, Kantrowitz E (2002). Socioeconomic Status and Health: The Potential Role of Environmental Risk Exposure, Annual Review of Public Health 23, 303-331.

Ewing R, Schieber RA, Zegeer CV (2003). Urban sprawl as a risk factor in motor vehicle occupant and pedestrian fatalities, Am J Public Health 93, 1541-5.

Farfel MR, Orlova AO, Lees PS, Rohde C, Ashley PJ, Chisolm JJ Jr (2003). A study of urban housing demolitions as sources of lead in ambient dust: demolition practices and exterior dust fall, Environ Health Perspect 111, 1228-34.

Friedman, Eric (2003). Vacant Properties in Baltimore: Strategies for Reuse. Johns Hopkins University. Abell Foundation Award in Urban Policy.

Greenberg MR (2002). Should housing be built on former brownfield sites? Am J Public Health 92, 703-5.

Greenberg MR (2003). Reversing urban decay: brownfield redevelopment and environmental health, Environ Health Perspect 111, No. 2, pp. A74-5.

Harlan, H (2000). O'Malley targets tech, Baltimore Business Journal, May 19-25.

Harvey PD (1990). Educated guesses: health risk assessment in environmental impact statements. Am J Law Med 16, 399-427.

History: Love Canal (2003). Environmental Protection Agency, November 2. Kid Friendly Cities Report Card (2000). Kid Friendly Cities wesbite: December 10, 2003.

Levine MV (1987). Downtown Redevelopment as an Urban Growth Strategy: A Critical Appraisal of the Baltimore Renaissance, Journal of Urban Affairs 9, 103-123.

Litt JS, Burke TA (2002). Uncovering the historic environmental hazards of urban brownfields, J Urban Health 79, no. 4, pp. 464-81.

Litt JS, Tran NL, Burke TA (2002). Examining Urban Brownfields through the Public Health 'Macroscope,' Environmental Health Perspectives 110, suppl 2, 183-93.

Maryland Dept of the Environment (2003) Air Quality 101. November 3.

Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Vital Statistics Administration (2002). Vital Statistics Annual Reports.

[NEPA] National Environmental Policy Act (2003). Environmental Protection Agency, November 12.

Partnership for Parks (2003). Baltimore City Dept of Recreation and Parks, December 9.

Paull, Evans, Director of Brownfield Initiative, Baltimore City Development Corporation (2003). Personal interview. November 12.

(PCA) Federal Environmental Pesticide Control Act of 1972 (2003). US Fish and Wildlife Service, December 10.

Pelton T, Streeter K (2000). Industrial heart of Baltimore beats to a new rhythm, Baltimore Sun. May 7.

Perdue WC, Stone LA, Gostin LO (2003). The built environment and its relationship to the public's health: the legal framework, Am J Public Health 93, No. 9, pp. 1390-94.

Perlin SA, Wong D, Sexton K (2001). Residential proximity to industrial sources of air pollution: interrelationships among race, poverty, and age, J Air Waste Manag Assoc 51, 406-21.

PlanBaltimore! Draft, Executive Summary (1999). Baltimore City Dept of Planning. April.

RCRA Cleanup (2003). EPA, December 10. Reinvesting in our industrial heritage (2003). Rhode Island Brownfields. December 10.

Ritz B, Yu F, Fruin S, Chapa G, Shaw GM, Harris JA (2002). Ambient air pollution and risk of birth defects in Southern California, Am J Epidemiol 155, 17-25.

Robbins, Michael (2004). Bizarre Bacterium Dines on Toxic Waste. Discover, Jan. 25, no. 1, 40.

Schoenbaum, M (2002). Environmental contamination, brownfields policy, and economic redevelopment in an industrial area of Baltimore, Maryland. Land Economics 78, 60-71.

Synder, RG (2000). Baltimore's tech industryemerges from shadows. Washington Techway, May 8.

Solitare L, Greenberg M (2002). Is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency brownfields assessment pilot program environmentally just? Environ Health Perspect, 110, 249-57.

Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act, H.R. 2869 (2001). Environmental Protection Agency. December 10, 2003. Sun staff (2000). Is a digital harbor in Baltimore's future? Baltimore Sun, March 26. Superfund (2003). Environmental Protection Agency. November 1.

Svitil, Kathy (2003). Got Pollution? Get Rust. Discover 24.

(TSCA) Toxic Substances Control Act (2003). EPA, December 10.

Turning Brownfields Green Again (1996). Environ Health Perspect 104, 371-2.

Urban air pollution linked to birth defects (2002), J Environ Health 65, 47-8.

(VCP) Voluntary Cleanup Program (2003). Maryland Department of the Environment, December 10.

Woodruff TJ, Parker JD, Kyle AD, Schoendorf KC (2003). Disparities in exposure to air pollution during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 111, 942-6.

Appendix

Suggested Optimal Redevelopment Strategies for Baltimore

Among the various development options of industry, service-based commerce, housing & community, and greenfields & parks , there should not be an all-and-nothing-else push down just one or two pathways of development. Rather, redevelopment directions should take into account all the various needs of local communities as well as the macroeconomics of Baltimore as a whole.

As discussed in the pros and cons sections, each aspect is complicated, though there most important issues to highlight in each of the four developmental pathways. Industry does bring pollution risks as well as potential recontamination. However, the author believes the immediate local impact of providing a large number of jobs to low-skill workers is very important for a city like Baltimore. Therefore, such brownfield redevelopments should possess highs levels of environmental monitoring as well as specially designed safe industrial parks. Additionally, industrial redevelopment should constitute approximately 30%-35% of remediated brownfield sites, rather than over 50%. The lower target percentage would not only still provide a significant proportion of low-skill labor, but it would also account for the declining industrial base nationwide that Baltimore would not be trapped with 50% vacancies nor equally dramatic numbers of layoffs in the future.

In terms of service-based financial, technology, and biotech commerce, Baltimore should definitely continue on its course to pursue such modern economic ambitions. However, at this point in time with the overall low-education and low-skill labor population in the city, Baltimore should also devote 50% of its cleaned-up brownfield sites to such commerce companies. This 50% is slightly inflated due to the incorporation of higher-skill suburban commuter laborforce.

But in terms of improving Baltimore's future economic transition and adjustment to the declining industry sector and rising technology sector, education and community empowerment should be an adamant priority for future generations to ensure that Baltimore's population is properly prepared for jobs of this new century. The urban affairs analyst Marc Levine (1987) agrees in such sentiments that planners in Baltimore should not just focus on establishing countless small short-term economic incentives to attract companies , but that a "dualism" approach can serve to achieve the same purpose. By first focusing to enhance upstream factors of improving education, SES, public services, and infrastructure (like mass transportation), Baltimore can in turn offer a higher-skilled labor force, and thus be better able to compete for business in the long run and simultaneously have a more prosperous population.

Meanwhile, housing should currently compose only 10% of brownfield redevelopment, due in large part to the high vacancy rates of houses in the city. It should additionally be clarified that the 5-8% of the sites that do undergo housing development, they should only be devoted to high density condominium housing on waterfront areas where it can attract higher-SES residents into Baltimore, and also which have limited hazard of toxic exposures from potentially inadequate cleanup due to the nature of the high-rise design.

However, of the 10% sites designated for housing and community development, a select few of them that are located close to residential areas should also be designated for grocery retailers and other small retailers needed for the function of a local community. Other than such exceptions, remediated sites should only be designated for high-density housing around popular waterfront areas that can attract high-income residents.

It is also important to note that recommending of housing limitation to only condominiums in wealthy areas does not at all mean that residential housing problems of dilapidation and lead contamination should be ignored in Baltimore. Low-density single unit housing have high potential of vestigial contamination exposure, as well as being unfortunate such renovation and redevelopment issues of old housing typically fall outside the purview of the brownfields.

Finally, though green-spaces and parks are attractive redevelopment prospects and can offer benefits of higher land value and neighborhood remediation, they are low-priority land investments currently in Baltimore, where more immediate stimulus is needed in the economy. Therefore, expansion of parks to include less than 5% of remediated sites would indeed be a reasonable estimate.